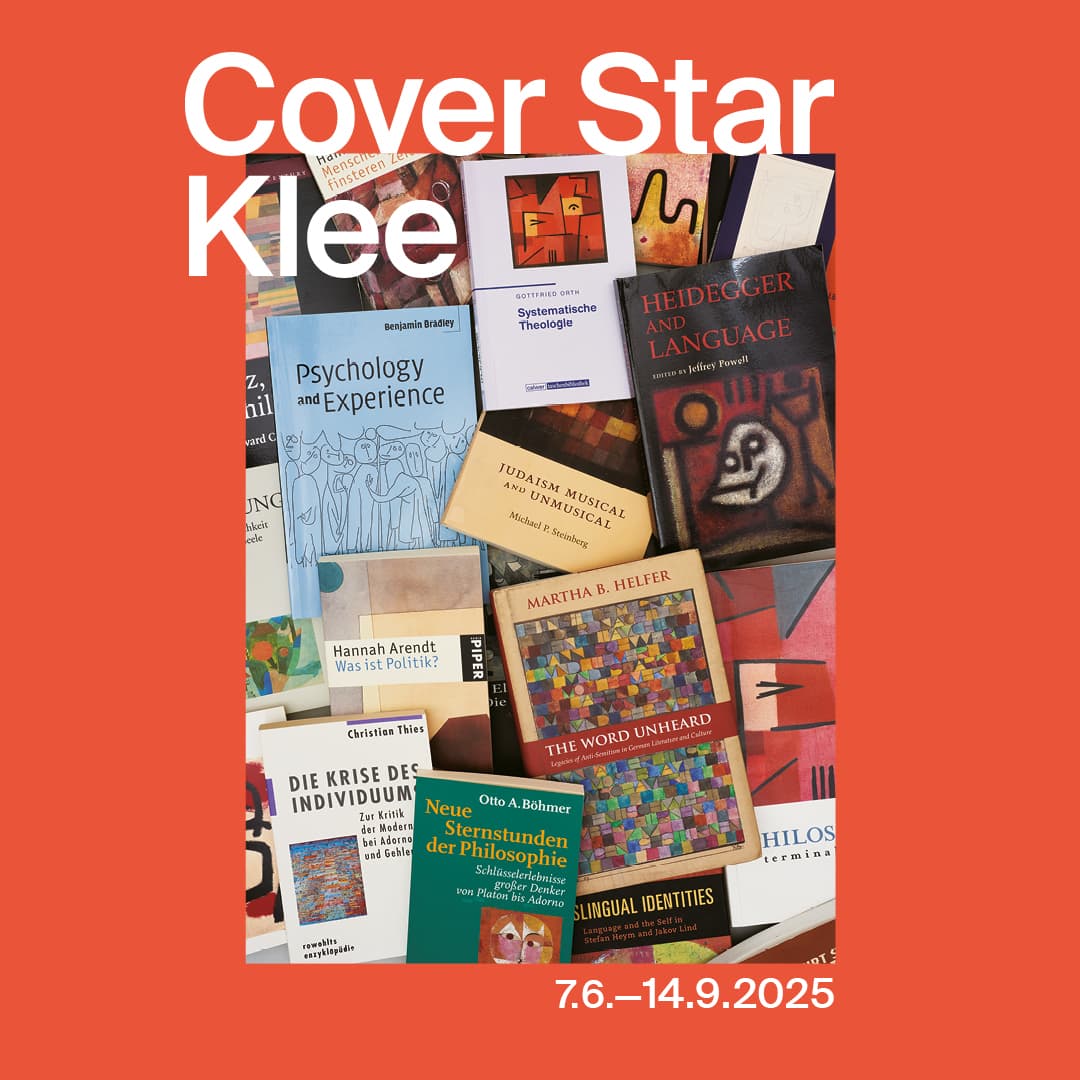

Paul Klee is one of the most influential artists of the twentieth century. Judging by his enduring popularity as the source of choice for book cover designs within a particular province of the publishing business, he is also one of the most influential artists of the twenty-first century.

Indeed, why do authors and/or publishers in the field of twentieth-century philosophy, so-called “theory” (capital-T Theory), and associated realms of the humanities (psychology, sociology, theology, therapy) so often turn to Paul Klee – often even the same Paul Klee painting, over and over again – to adorn the covers of their books? In bringing together hundreds of books sourced from the Zentrum Paul Klee’s own library and beyond, most of which were published in the last two decades, Cover Star Klee offers some speculative, tentative answers to this question. Perhaps theorists of our cultural moment are drawn to Klee for his love of all that is minute and microscopic; they might think of him as the exemplary poet of fragmentation, a chronicler of confusion and disarray. Perhaps Klee’s unheroic brand of abstraction exemplarily suits the inchoate anxieties of our rudderless here and now; perhaps nothing encapsulates the riddle of German-Jewish relations quite as powerfully as Klee’s startled Angelus Novus.

In pairing said book covers with corresponding original drawings and paintings, Cover Star Klee proffers a light-hearted look at what is best known today as “meme culture”. Far from being an indictment of the visual poverty of the publishing imagination in said academic fields, Cover Star Klee honours the power of a select handful of artistic images and their spellbinding grip on the twentieth- (and twenty-first) century’s intellectual imagination.

This exhibition was organized by Dieter Roelstraete, curator at the Neubauer Collegium for Culture and Society at the University of Chicago. Originally trained as a philosopher, Roelstraete’s curatorial work focuses on the relationship between art and knowledge. In 2019 he authored the book Kleine Welt (see book table), which light-heartedly explores the significance of the book cover – centered on the work of Paul Klee.

The title, year and number of the Klee work are noted on the bookmarks on the cover.

Angelus Novus: Paul Klee and Walter Benjamin

Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus has become the symbol par excellence, it seems, of the triumphs and tragedies of twentieth-century German-Jewish culture. This iconic little oil-transfer drawing, made by Klee in 1920 – in between his dismissal from wartime military service and his appointment at the Bauhaus – and now owned by the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, is best known through its association with the work of the German-Jewish philosopher Walter Benjamin, who bought it from the Munich art dealer Hans Goltz for the tidy sum of 1,000 marks in late spring 1921. (Already in 1920, Benjamin’s wife, Dora, had given her husband a Klee work as a birthday present, namely the watercolour Vorführung des Wunders (Introducing the Miracle) from 1916, now in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York.)

That same year, Benjamin founded a literary journal titled Angelus Novus in an “attempt to draw a connection between the artistic avant-garde of the period and the Talmudic legend about angels who are being constantly created and find an abode in the fragments of the present.” (Klee was not Jewish and never met Benjamin; we do not know what Klee thought – if anything – of the critic’s theologically charged interpretation of this youthful work.)

Klee’s whimsical winged creature clearly ranked among Benjamin’s most prized possessions, keeping him company throughout his nomadic, tragically short life. Shortly before fleeing Paris in the summer of 1940 on his way to the small Pyrenean border town of Port Bou, where he would meet his chosen end, he included Klee’s seraph in a cache of papers entrusted to a librarian at his beloved Bibliothèque Nationale called Georges Bataille. After the war, Benjamin’s possessions were somehow passed on to his Frankfurt School colleague Theodor Adorno in New York, who later transferred them to Benjamin’s Weimar-era friend Gershom Scholem, the revered historian of Jewish mysticism in Israel. After Scholem’s death in 1982, Klee’s oil transfer drawing was finally gifted by the former’s widow to the Israel Museum – resulting in the first public viewing in more than half a century of a work only known, until then, through its enigmatic invocation in the ninth paragraph of Benjamin‘s abstruse intellectual testament “Theses on the Philosophy of History” (1940): “A Klee painting named Angelus Novus shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past.” Was Benjamin’s guardian angel a Klee portrait of sorts?

Kleinwelt (Little Cosmos): Paul Klee and the Publishing Business

Kleinwelt is the title of an etching made by Paul Klee in 1914, but only published in 1918, when it was included in a portfolio of prints issued by Kiepenheuer Verlag’s periodical Die Schaffenden (The Creators). The four years between the making and the printing of this diminutive work, of course, belonged to World War I – two years of which Klee spent in uniform and active military duty, though blessedly far from the front (unlike his close friends and colleagues August Macke and Franz Marc, who died in the early years of a military conflict that utterly transformed the world as they had come to know it). The teeming microcosm of creepy-crawly movement at the heart of Kleinwelt ominously presages the apocalyptic chaos and disorienting murk of trench warfare – though when reproduced on the cover of a book titled Kleine Welt edited by the curator of the present exhibition, it primarily alludes to the “little world” of academic book publishing, which so often turns to Paul Klee to visualize hard-to-image concepts such as “difference”, “reason”, “revelation”, “risk” and other keywords from the sprawling Kleinwelt of “theory”.

Paul Klee, it turns out, is the philosopher’s painter par excellence, bringing the verbose world of abstract thought to chattering visual life in book cover after book cover. As the art historian Annie Bourneuf put it in her exemplarily titled study Paul Klee: The Visible and the Legible, “the pursuit of analogies between writing and images, the solicitation of a reading-like mode of viewing,” are central to Klee’s art. (Consider the closing sentence of paragraph no. 3 in the artist’s oft-reprinted “Creative Confession”, first published in 1920: “In the beginning is the act; yes, but above it is the idea. And since infinity has no definite beginning, but is circular and beginningless, the idea may be regarded as the more basic. In the beginning was the word, as Luther translated it.”)

Kleine Welt is also the title of an exhibition first presented at the Neubauer Collegium for Culture and Society at the University of Chicago in 2019, from which the idea for Cover Star Klee was born; that exhibition consisted of a mere 60 books with Paul Klee-inspired covers. Cover Star Klee could easily have contained 600 books – though that would contravene the spirit of Klee’s work, which was so singularly devoted to honouring the small.

Betroffener Ort (Affected Place): Paul Klee and the Bauhaus

The American philosopher and cognitive scientist Daniel C. Dennett clearly loved Paul Klee: four of his books – and his best known, most widely read among them – sport Paul Klee paintings on their covers. It seems fair to assume that these must have been authorial choices as much as editorial ones: in the most recent of these books, Intuition Pumps and Other Tools for Thinking, Dennett actually references Klee as one of the presumed authors of the phrase “to make the familiar strange”, which he calls one of the “self-appointed tasks” that both artists and philosophers agree to share: “among those credited with the aphorism are the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, the artist Paul Klee, and the critic Viktor Shklovsky.” (Come to think of it: why haven’t there been more books about Wittgenstein with Paul Klee covers? They, too, seem made for each other.)

Betroffener Ort was painted in 1922, during Klee’s formative tenure at the Bauhaus, where he met Wassily Kandinsky again, the Russian “inventor” of abstract art. The painting’s titular “affected place” may refer to the jumble of fence-like curlicues in the centre of the image – a deserted village square or garden? A patch of interiority? – impacted by a bold, fairly menacing arrow thundering its way down the horizon like a lightning bolt or the sword of Damocles. Klee himself understood this impact in geological terms, calling the play of horizontals and verticals in this painting a fault line: “the arrow’s target is the centre of the earth” – the citadel of certainty, perhaps, of the preconceived notions that constitute the life of the mind as we know it. Betroffener Ort certainly ranks among Klee‘s more “aggressive” works; the contrarian charge of its angular energy resembles the true hardness of all thought that seeks to “make the familiar strange”, so central to the mission of modern art as it was hatched out in sites such as the Bauhaus. It is perhaps Dessau, then, that is the truly “affected place”.

Hauptweg und Nebenwege (Highway and By-Ways): Klee and Critical Theory

The intuitive association of Paul Klee’s art with Critical Theory and the philosophy of the so-called Frankfurt School in particular stretches well past the romantic saga of Walter Benjamin’s Angelus Novus, as is attested by the many histories of said School that take recourse to classic Klee imagery to peddle their wares. Klee’s iconic Hauptweg und Nebenwege from 1929, for instance, seems well-nigh custom-made to illuminate the ideas of Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, Herbert Marcuse et al. – much like the cruder, more primitivist work of the 1930s is so often a peerless match for the correspondingly “crude” and wilfully “primitivist” philosophy of the Frankfurters’ long-time antagonist Martin Heidegger. What better way to “illustrate” the notion of critique as theory, or of theory as critique, than by way of an image depicting myriad “byways” (cf. the Adornian tactic of diversion) crowding around a single mono-minded “highway” (cf. the Heideggerian myth of a knowable origin)? Hauptweg und Nebenwege is perhaps the closest Klee ever came to capturing in paint the capricious, shimmering essence of dialectics, of the “dialectical imagination” at work, to paraphrase the title of Martin Jay’s landmark history of the Frankfurt School. (In his Aesthetic Theory, Adorno memorably observed that the literal greatness of Klee resides in his talent for miniaturization.)

David Held’s slightly later history of the Frankfurt School concludes with a long last look at Homer’s Odyssey, a touchstone of Adorno and Horkheimer’s theorization of “instrumental reason” as recounted in their seminal Dialectic of Enlightenment: “Homeland is, of course, the telos of the Homeric journey,” Held writes. “Odysseus’ return, anticipating the possible homecoming of Western human beings, is to a life ‘wrested from myth.’ His home, however, does not allow us to forget the horror of his journey. Nor do we forget that the home is his. The Odyssean homecoming might promise reconciliation between people and nature, and between people and one another, but it remains a promise – it awaits actualization.” It flickers on the horizon, like the Nile in the midday heat as Paul Klee chose to paint it here – and many roads may lead to it: the less well travelled, the better.

Alter Klang (Ancient Harmony): Paul Klee and Music

Cover Star Klee focuses on the use of Paul Klee’s imagery in book design, specifically of the academic and/or theoretical variety. However, one could just as well imagine an exhibition such as this centred solely on Paul-Klee-inspired record covers – for Klee’s art is a comparably dependable source of imagery, it seems, for rendering sound as vision, and one will unsurprisingly find Klee’s drawings and paintings grace a good number of recordings of early twentieth-century classical music and “abstract” jazz in particular. Evidently, the well-established notion of Klee’s “musicality” – the sense one gets of Klee’s world as a sonic universe rendered in colours and lines instead of notes and tones – is rooted in part in the artist’s biography: Klee’s German father was a music teacher, his Swiss mother a singer, and he initially appeared destined to become a musician, picking up the violin and bow long before mastering the paintbrush and pen.

Already in the 1910s, Klee famously remarked: “One day I must be able to improvise freely on the keyboard of colours: the row of watercolours in my paint box.” That said – and here his iconic Alter Klang from 1925 appears programmatically titled – his musical taste remained thoroughly conventional, conservative even: Bach and Mozart, as opposed to the jagged modernism of composers like Hauer, Hindemith, Schoenberg, or Stefan Wolpe (who just happened to be a student at the Bauhaus during Klee’s highly influential mid-twenties tenure there), whom we are perhaps more likely to hear when looking at, and listening to, paintings such as this muscular experiment in geometric abstraction. (Alter Klang dutifully appears on the cover of a recording of Paul Hindemith’s clarinet-led chamber music as well as on an album of Takashi Kako’s Third Stream-tinged jazz titled Klee.)

A book by Michael P. Steinberg titled Judaism Musical and Unmusical successfully maps the putative converging of the purported “Jewishness” and musicality of Klee’s work in its use of Alter Klang; the title of Steinberg’s book is a partial riff on Max Weber’s quip, “Ich bin religiös unmusikalisch”: I am unmusical in matters that regard religion. Klee’s subtly shape-shifting grids of the 1920s, on the contrary, evoke an image of music as the modern world’s go-to secular religion.

Constructiv-impressiv (Constructive-Impressive): Paul Klee and Hermann Hesse (via Jacques Derrida)

Constructiv-impressiv, interestingly, is the only painting referenced by name in Jacques Derrida’s landmark (and contentious) The Truth in Painting: a book that appears to be “about” art, but that is really much more “around” art; a book about frames rather than the pictures framed within (La vérité en peinture was published in 1979, the highwater mark of postmodernism); a book about the institutions that produce the experience of art as we know it – all the way from the studio and the museum to the nails, presumably, from which a painting could be hanging. Derrida (of whom one might legitimately ask: why don’t we see more Klee paintings on his book covers?): “When nails are painted (as they are by Klee in his Constructiv-impressiv of 1927), as figure on a ground, what is their place? To what system do they belong?” These are great, probing questions – but is it really nails we are seeing in Klee’s painting as shown on the cover, for instance, of an early seventies Penguin paperback edition of Hermann Hesse’s The Glass Bead Game, the Nobel Prize-winning author’s last novel (begun in 1931 but completed in exile and only published in Switzerland in 1943)?

Hesse and Klee were born less than two years apart (the former in 1877, the latter in 1879), in Southwestern Germany and the Swiss Central Plateau, respectively – Hesse a German who became a Swiss writer, Klee a Swiss who became a German artist. Klee wrote poems (which were only published after his death) while Hesse painted watercolour landscapes. Yet somewhat improbably, they never met – the closest they came to crossing paths was in Hesse’s 1932 novella Die Morgenlandfahrt (translated as “Journey to the East”), where Klee makes an appearance as a fictional character alongside Plato, Don Quixote, Mozart, Baudelaire, and a certain Klingsor – the Expressionist painter-character at the centre of Hesse’s 1920 novel, Klingsor’s Last Summer.

The Glass Bead Game has also been published under the Latin title Magister Ludi, “master of the game” – about which Hesse noted the following: “These rules, the sign language and grammar of the Game, constitute a kind of highly developed secret language drawing upon several sciences and arts, but especially mathematics and music (musicology respectively), and capable of expressing and establishing interrelationships between the content and conclusions of nearly all scholarly disciplines. The Glass Bead Game is thus a mode of playing with the total contents and values of our culture; it plays with them as, say, in the great age of the arts a painter might have played with the colours on his palette.”

Tod und Feuer (Death and Fire): Paul Klee and Martin Heidegger

Tod und Feuer is one of the last works Paul Klee ever painted, finished shortly before his death on June 29, 1940. It is part of a larger group of works made after the onset of scleroderma in the mid-1930s, a medical condition that severely weakened Klee’s command of the finer aspects of image-making; many of the paintings made in the last years of his life are marked by a quasi-hieroglyphic, graphic crudeness. (Pharaonic Egypt, along with prehistoric cave art, had been an iconographic interest of his for some time as well.) The death mask at the centre of this rough-and-ready painting on coarse, untreated jute may have been a self-portrait – the artist readying himself for the end announced in the dance of the letter-like features of the grinning skull (the T, o and upside down d of the German word for death). At the time of the painting’s completion in neutral Switzerland, death, of course, was encircling Klee on all sides; the German cities that he had so long called home would soon be reduced to smouldering ash.

A perennial ghoulish favorite at the Zentrum Paul Klee, it was most likely included in the Klee survey show that the disgraced German philosopher Martin Heidegger came to visit in Bern in 1956 – a dark time, in turn, for the fallen idol of Todtnauberg. (Before Heidegger met the Romanian-Jewish poet Paul Celan in his rustic mountain retreat there in the late 1960s, the latter had already become famous for naming death “a master from Germany.”) Exposure to Klee’s work after the war famously compelled Heidegger to briefly consider rewriting parts of his seminal essay “The Origin of the Work of Art” from 1936. Nothing ever came of the plan, which remained stuck in a haphazard pile of “Notizen zu Klee” – one of which includes a memorable Klee quote: “Bilder sind keine lebenden Bilder” – images are not living images; paintings are dead: non-beings. This Klee painting in particular must have appealed to Heidegger in its frank embrace of “Being-towards-death,” as he was fond of characterizing one of the fundamental qualities of authentic Dasein.

The sternly clenched jaw marking the Totenkopf in the middle of the painting has made this artwork a beloved, natural motif for a number of publications on the morbid topic of “late style”, and there could hardly be a more fitting seal for the unison of Heidegger and language in death than Klee’s famous last strokes.

Senecio: Paul Klee and Senescence/Silence

The painting Senecio, also known under the title Head of a Man Going Senile, shows Klee at his most whimsical and humorous, revealing something of Klee’s spiritual debt to the gentle, ludic anarchism of Zurich Dada. Though there are obvious echoes of African mask art and cubism to be discerned in this crude, cartoonish portrait of a “tiny old man”, the more revealing point of comparison might be that of the vibrant satirical tradition flourishing in Germany at the time – think, for instance, of George Grosz’s scathing caricatures of the pillars of Weimar society, which were so often rendered as “men going senile”. The year 1922 was particularly productive for Klee, but also a very momentous one in Germany’s immediate postwar period, witnessing the assassination of Walther Rathenau and the dizzying depreciation of the mark, which would help pave the way for a proliferation of extremist political discourse culminating in Adolf Hitler’s Beer Hall Putsch of 1923. (Is that a tiny, neatly trimmed moustache we’re seeing, or are those just Senecio’s nostrils?) Klee’s petit vieillard does seem a little disgruntled, perturbed: the familiar face of aggravation – the fitting cover star, therefore, of Robert C. Solomon’s True to Our Feelings: What Our Emotions Are Really Telling Us, the first chapter of which is titled “Anger as a Way of Engaging the World”. How very contemporary Klee’s angry old man appears to us in our current age of rage, which has sparked more than one casual comparison with Germany’s date with destiny in the accursed year 1933.

Senecio also appears on the cover of a book devoted to the work of Stefan Heym and Jakov Lind, two relatively little-known German-Jewish authors who published primarily or exclusively in the English language of their adopted homes and postwar (“translingual”) identities. The author claims the language of these novelists’ choice as the only roof above their head. Interestingly, Klee’s tiny old man does not appear to have a mouth to speak of: no language for him, born of the linguistic tumult of 1920s Central Europe. How telling that Klee painted this picture in the same year James Joyce’s Ulysses – the ultimate tale of the “Wandering Jew”, in the guise of Leopold Bloom, as loquacious everyman (Heym actually wrote a book titled Ahasver, in 1981) – was first published in a tiny print run in Paris.

Blick aus Rot (Glance out of Red): Paul Klee and Psycho-analysis/-logy/-therapy

Blick aus Rot – sometimes tendentiously translated as Beware of Red, which sounds decidedly political in the context of its making (1938) – is one of Paul Klee’s late paintings: only a little less demonstratively aware of the nearing end, perhaps, than his Death and Fire, with which it shares a rudimentary (and ill-omened) sense of scattering and fragmentation. (Paul Klee is the supreme poet of fragmentation as the defining philosophical experience of modernity – of the fragment as the sacrament of modern thought.)

Like so much of Klee’s art, this painting invites interpretive projections of all types, so it only seems appropriate that a reproduction of Blick aus Rot, so disorienting and centreless and open to analysis, should appear on the cover of a book by Jonathan Lear titled Open Minded: Working Out the Logic of the Soul, conceived (in part) as a critical plea for a retour à Freud as an inexhaustible source for achieving a better understanding of the structure of human subjectivity in our age of “knowingness.” Thinking and writing at the intersection of philosophy and psychoanalysis, Lear remarks in his preface to Open Minded: “Psychoanalysis, Freud said, is an impossible profession. So is philosophy. This is not a metaphor or a poetically paradoxical turn of phrase. It is literally true. And the impossibility is ultimately a matter of logic. For the very idea of a profession is that of a defensive structure, and it is part of the very idea of philosophy and psychoanalysis to be activities which undo such defences. It is part of the logic of psychoanalysis and philosophy that they are forms of life committed to living openly – with truth, beauty, envy and hate, wonder, awe and dread.” To open not just the mind, but body and soul – and Eye and I alike.

The exact nature of Paul Klee’s relationship to Freud and psychoanalysis is too unwieldy a subject to map out here, but Klee’s enduring popularity as a purveyor of imagery deemed singularly well-suited to “illustrate” various tenets of various “logics of the soul” (psychologies, psychotherapies) is plain for all to see – and the entanglement of seeing and understanding may be integral to this circumstance: the essence of Klee’s work may well reside in its foundational resistance to identifying “essences” – in its programmatic, never-tiring opening-up of the field of vision.

Imprint

Fokus. Cover Star Klee

Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern

7.6. – 14.9.2025

Digital Guide

Implementation: Netnode AG

Project Management: Dominik Imhof

Curator and Texts: Dieter Roelstraete

Translation: Sarah McGavran

The Zentrum Paul Klee is fully accessible and offers inclusive events.